- December 11, 2024

- Posted by: Precious David

- Category: Uncategorized

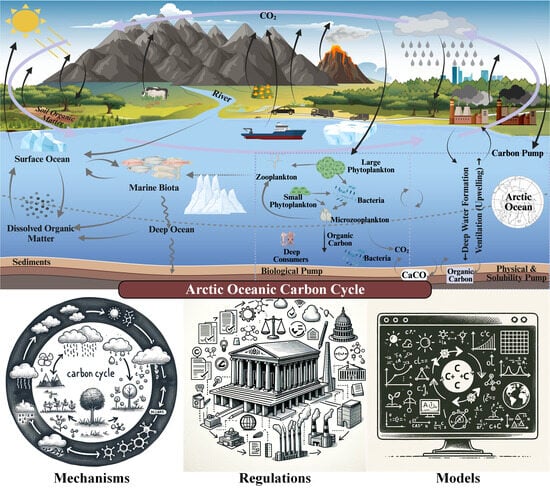

For thousands of years, the Arctic has served as one of the planet’s most reliable carbon sinks. The permafrost—a layer of frozen soil and organic material—locked away vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane, preventing them from entering the atmosphere. However, the narrative of the Arctic as a climate stabilizer is shifting dramatically. Due to wildfires and the thawing of permafrost, the Arctic may now be releasing more carbon dioxide than it absorbs, marking an unprecedented and troubling change.

The Role of Thawing Permafrost

Permafrost, which underpins much of the Arctic landscape, contains nearly twice as much carbon as the atmosphere. As global temperatures rise—with the Arctic warming at roughly four times the global average—permafrost is thawing. This process activates microbial activity that decomposes organic matter, releasing CO2 and methane. Methane is particularly concerning because it’s a greenhouse gas over 25 times more effective at trapping heat than CO2 over a 100-year period.

A study published in *Nature Communications* in 2023 revealed that thawing permafrost could release 50-100 gigatons of carbon by the end of the century if emissions remain unchecked. This release could transform the Arctic from a carbon sink into a significant carbon source, compounding the challenges of climate mitigation.

The Role of Wildfires

In recent years, Arctic wildfires have become more frequent and intense. These fires, often fueled by dried vegetation and exacerbated by warming temperatures, release vast quantities of CO2 directly into the atmosphere. According to the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, Arctic wildfires in 2020 alone emitted approximately 244 megatons of CO2, equivalent to the annual emissions of countries like Spain.

Furthermore, wildfires can accelerate permafrost thaw by removing insulating vegetation and exposing the soil to warmer temperatures. This creates a feedback loop—more wildfires lead to more permafrost thaw, which in turn leads to increased carbon emissions.

The First Time in Thousands of Years

Paleoclimate records suggest that the Arctic has acted as a carbon sink for millennia, absorbing more carbon than it emitted. The current shift, driven by anthropogenic climate change, could represent the first time in thousands of years that the region is a net carbon emitter. This change underscores the fragility of the Arctic’s carbon cycle and its growing role in driving global warming rather than mitigating it.

Implications for the Global Climate

The Arctic’s transition from a carbon sink to a source has far-reaching implications. Increased carbon emissions from this region could accelerate global temperature rise, making it harder to achieve international climate goals like those outlined in the Paris Agreement. Additionally, this shift could exacerbate extreme weather events, sea-level rise, and biodiversity loss worldwide.

What Can Be Done?

Mitigating this crisis requires immediate and concerted global action:

1. Reduce Fossil Fuel Emissions: Cutting greenhouse gas emissions is critical to slowing Arctic warming and permafrost thaw.

2. Promote Fire Management: Investing in Arctic wildfire prevention and control measures can help limit CO2 emissions and protect permafrost.

3. Support Research and Monitoring: Enhanced monitoring of Arctic carbon dynamics is essential for understanding the extent of emissions and developing targeted interventions.

4. International Cooperation: The Arctic’s fate impacts the entire planet, requiring collaboration among nations to address this shared challenge.

The Arctic’s emerging role as a carbon source is a stark reminder of the cascading impacts of climate change. As thawing permafrost and intensifying wildfires release unprecedented amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, the urgency for action cannot be overstated. Protecting the Arctic—and by extension, the global climate—demands swift, science-based policies and a commitment to sustainability from all corners of the globe.

—

References

– Schuur, E. A. G., et al. (2015). Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature.

– Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. (2020). Arctic wildfires emissions report.

– Turetsky, M. R., et al. (2020). Carbon release through abrupt permafrost thaw. Nature Communications.

– Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Sixth Assessment Report.